A Wolff in sheep’s clothing: Trabecular bone adaptation in response to changes in joint loading orientation

Most loading to bones is axial but there is always some non-axial loads as the bones have shape thus there is a mix of tensile, compressive, and torsional loading. But loading bones in one axis will tend to produce the same stimuli, whereas doing things like lateral and torsional will induce unique stimuli. This will produce more effective adaptations including possibly growing taller if the loading is sufficient.

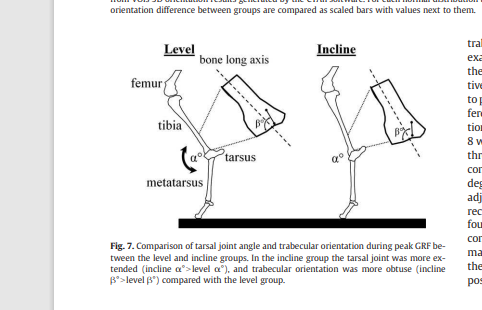

“This study tests Wolff’s law of trabecular bone adaptation by examining if induced changes in joint loading orientation cause corresponding adjustments in trabecular orientation. Two groups of sheep were exercised at a trot, 15 min/day for 34 days on an inclined (7°) or level (0°) treadmills. Incline trotting caused the sheep to extend their tarsal joints by 3–4.5° during peak loading (P b 0.01) but has no effect on carpal joint angle (P= 0.984). Additionally, tarsal joint angle in the incline group sheep were maintained more extended throughout the day using elevated platform shoes on their forelimbs. A third “sedentary group” group did not run but wore platform shoes throughout the day. As predicted by Wolff’s law, trabecular orientation in the distal tibia (tarsal joint) were more

obtuse by 2.7 to 4.3° in the incline group compared to the level group;{Can this change in trabecular orientation effect bone length?} trabecular orientation was not significantly different in the sedentary and level groups. In addition, trabecular orientations in the distal radius (carpal joint) of the sedentary, level and incline groups did not differ between groups, and were aligned almost parallel to the radius long axis, corresponding to the almost straight carpal joint angle at peak loading. Measurements of other trabecular bone parameters revealed additional responses to loading, including significantly higher bone volume fraction (BV/TV), Trabecular num-ber (Tb.N) and trabecular thickness (Tb.Th), lower trabecular spacing (Tb.Sp), and less rod-shaped trabeculae (higher structure model index, SMI) in the exercised than sedentary sheep.

Overall, these results demonstrate that trabecular bone dynamically adjusts and realigns itself in very precise relation to changes in peak loading direction{it’s also possible that mixing up axial, lateral, and torsional loading could cause the trabecular to have to constantly dynamically adjust}, indicating that Wolff’s law is not only accurate but also highly sensitive”

“changes in posture will alter stress distribution within the bone and eventually, if they persist, the trabecular structure will readjust to the new stress trajectories.”

The paper mentions that different locomotive methods induce changes in trabecular orientation.

“As intended, the angle of the tarsal joint was more extended by 3.6° at

the time of peak GRF (midstance) in the incline group”

From the looks of this image the incline group looks like it stands taller even though bone length may be the same.

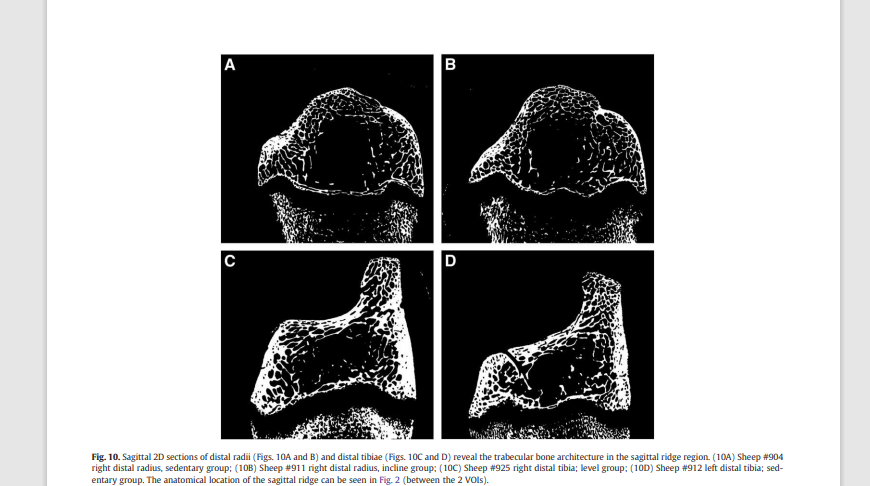

“a minimum level of loading is necessary to affect trabecular growth is evident from the almost total lack of trabeculae documented in the sagittal

ridges of the distal tibia and radius”<-So there must be sufficient weight used in lateral and torsional loading regimes.

“An additional limitation is that we studied only very young animals whose joints were still growing and remodeling.”

Note how much bigger and longer the epipihysis is in image B versus A but again these are growing animals. They said that trabecular did not really change much in the radius(groups A and B) but the two radius look much bigger.

In contrast the Group D looks smaller than group C which is the tibiae which is what changed.

Studies like Trabecular bone in the calcaneus of runners, were conducted on runners above age 20 so it’s likely still that trabecular bone is responsive to the direction of loading.

The paper Physical activity engendering loads from diverse directions augments the growing skeleton, shows that again loads from diverse directions are important thus perhaps typical axial loading is enough.

“Growing mice housed for three months in cages designed to emphasize

non-linear locomotion (diverse-orientation loading) were found to have enhanced trabecular and cortical bone in the proximal humerus compared to animals housed in cages that accentuated linear locomotion (stereotypic-orientation loading).”

These papers show why we must try to use experiment with lateral and torsional loading methods in attempts to grow taller.